News

The creation of an African ‘bloodstream’: Malaria control during the Hitler War, 1942–1945 (Part 2)

[This piece is culled from a book

authored by Jonathan Roberts, titled:

Sharing the burden of sickness: A history

of healing and medicine in Accra]

Cleansing Korle: The Allied Antimalaria Campaign of 1942–45

As the war in Europe began, the small garrison in Accra scrambled to secure the colony from an incursion from Cote D’Ivoire, Togo, or amphibious assault by sea. A curfew was imposed on the colony, with lights off at night and car headlights shuttered. As the Allied armies suffered defeat after defeat in Europe and Asia, fear of an aerial or naval bombardment of Accra grew. Rumours flew of German submarines shooting at fishermen. In the early months of the war, it became obvious that no new troops were coming to protect the Gold Coast, and only a small number of Royal Air Force planes were available to patrol the seas. Admitting that the home islands could do little to help the colonies, the British Secretary of State called on their subjects abroad to create their own Home Guards and to retreat according to a scorched-earth policy in case of invasion. Fear was in the air.

Fortunately for the residents of Accra, the Gold Coast never became a battleground during the war. However, Accra did become a hub of wartime activity when the British War Office chose the city as the Headquarters of the British West African Command. General Giffard was placed in command of the West African forces and turned Accra into a marshalling yard for goods and personnel departing for India. The arrival of thousands of soldiers from Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and the Gambia should have created a major health concern for the city, in terms of clean housing, a healthy food supply, and adequate medicines, but since the soldiers were shipped out to India so quickly, the city required no sanitary changes to accommodate their numbers.

In addition to housing the West Africa Command, the city became an aerial transshipment point for North Africa. In 1941, the German Army had cut off British troops in North Africa from their Mediterranean supply routes, forcing the Allies to send supplies across the Sahara Desert by air. Accra suddenly became home to a major Allied airbase. During the peak years of 1942–43, between two and three hundred aircraft landed daily at the airport for refuelling and maintenance, and thousands of airmen and airport crew were stationed in the city. To treat sick personnel, the British built the first military hospital near the airport, known officially as the 37th General Hospital of the British Empire, a segregated facility with 200 European beds and 800 African beds. The hospital was badly needed because by 1942 malaria rates among soldiers and airmen in Accra were startlingly high. British, American, and African soldiers all suffered, but the illness was particularly bad among White soldiers who had never been exposed to the disease. In 1942, morbidity rates exceeded 50 per cent per year, and an epidemic flare-up during that rainy season sent 62 per cent of Allied soldiers to the hospital for treatment. Worse still, Allied commanders feared the disease would spread from West Africa to the rest of the world. In the 1930s, 16,000 people in Brazil had died as a result of the introduction of Anopheles gambiae and its malaria parasites by ship from Dakar. Fearing another outbreak, the Brazilian government pressured the Americans to ensure that transport planes on the Atlantic routes did not harbour any mosquitoes. The British and American armed forces, who had not anticipated being so heavily invested in operations in West Africa, felt obliged to take steps to control malaria in Accra.

Part of the Allied concern about illness among personnel was a fear of losing valuable war matériel. By 1942, 25 per cent of the pilots flying from Accra to Egypt were landing in Cairo with malarial symptoms. Trained pilots were in short supply, and to ensure the safety of both the airmen and airplanes, it was crucial that the British keep them healthy during their short stay in Accra.

The Royal Air Force argued strongly for the case of a mosquito vector control scheme around the airport, claiming that “malaria control of an airfield (especially in the case of an essential airfield) shows a large credit, for the loss of only two or more heavy bombers, resulting from a poor landing by a pilot with malaria attack during the flight (a thing very liable to happen in high altitudes of flying when the pilot has parasites in his blood), more than pays for the cost of the scheme. The cost of a Superfortress is in the region of $600,000.” When stated in such plain logistical and financial terms, the need to stop the spread of malaria in Accra became obvious to the Allies.

Not surprisingly, American medical officials added a racial component to the discourse about malaria, expressing concern that Africans might infect White soldiers. For the US Army, segregation between the so-called races was a well-established protocol, so it was not surprising that they used the fear of disease to justify the separation of their soldiers from the African population of the Gold Coast. The British were less convinced that segregation was an appropriate strategy to fight malaria. They had already attempted to dismantle institutional segregation in the colony, and since quinine was widely available in pill form at colonial post offices or by injection at Korle Bu, they did not see the need to further divide the races. However, the rapid influx of troops and a dramatic increase in construction near the airport led to rates of malaria that the British had never seen before in Accra. The fear of epidemic malaria was further amplified when the Japanese invaded Java in the Dutch East Indies, cutting off the world’s largest source of natural quinine. By 1942, Allied malariologists were in agreement that they desperately needed a new strategy for controlling malaria in Accra, even if it required segregation.

To coordinate antimalaria efforts, the British Army brought Major O. J. S. Macdonald of the Indian Medical Services to Accra to serve as an official area malariologist. Macdonald was a specialist in wastewater treatment, and when he arrived in Accra he echoed Selwyn-Clarke’s belief that the Korle Lagoon was to blame, declaring it to be “swarming with Anopheline larvae” and he proposed that the two armies fund an antimalaria initiative along the Korle watershed. The Americans were receptive to the idea, but before they would sign on to a joint drainage programme, they brought their own specialist to the city to investigate the situation. Captain Lowell T. Coggeshall, a specialist in tropical medicine at the University of Michigan, joined forces with Macdonald in 1942, and the pair drew up a comprehensive plan that included changes to soldiers’ housing, alterations to their attire, and the excavation of 45 kilometres of viaducts and ditches around the city. Coggeshall and Macdonald brought together many other British and American physicians and scientists to create the Inter-Allied Malaria Control Group, and both the US Army and the British Colonial Office agreed to pay for the scheme. For the first time in the history of Accra, the personnel, equipment, and funding were in place to eliminate mosquito borne illnesses from the city.

The Allies’ first step was to restructure the living quarters of their troops. Following a pattern of segregation that had led to the development of suburbs like Victoriaborg and the Ridge, the Malaria Control Group set to work building an army residential area to the northeast of the city, next to the airport. The camp that housed the White soldiers was specifically located a mosquito flight away, judged to be one-quarter of a mile, from the nearby villages of Nima and Kanda. A change in attire soon followed the change in location, as the Allies adapted military apparel to better suit the disease climate. White British and American soldiers had arrived in Accra wearing their cold-weather uniforms, including greatcoats that had to be aired weekly to prevent mold. They were issued wool pajamas, which were unbearably hot, especially under a mosquito net. The soldiers soon abandoned these for cotton pajamas or for nothing at all. The Malaria Control Group remedied the problem by distributing warm-weather clothing, but they still required soldiers to wear long sleeves, trousers, and boots to prevent mosquito bites. Any leftover bare skin was to be covered with mosquito repellent. The Allies also changed the soldiers’ dormitories, installing screened windows and requiring soldiers to sleep under bed nets. To emphasise the need for vigilance, Allied film crew projected slides of cartoons onto screens at the barracks to exhibit the dangers of mosquito exposure. These images depicted the mosquito vector as a “fifth column” that, in collusion with the lazy soldier who neglected to mend his netting, would attack the troops in their sleep. In Accra, where there were no Axis soldiers to fight, the mosquito was the enemy.

News

New BoG governor can’t engage in official duties – Afenyo-Markin to Mahama

The Minority Leader, Alexander Afenyo Markin has raised concerns over the assumption of official duties by Dr. Johnson Asiamah as Governor of the Bank of Ghana (BoG).

The former Deputy Governor was recently nominated by President John Dramani, on January 31, 2025, to serve as Governor, pending approval by the Council of State.

This follows a formal request by the current Governor, Dr. Ernest Addison, to proceed on leave ahead of his retirement on March 31, 2025.

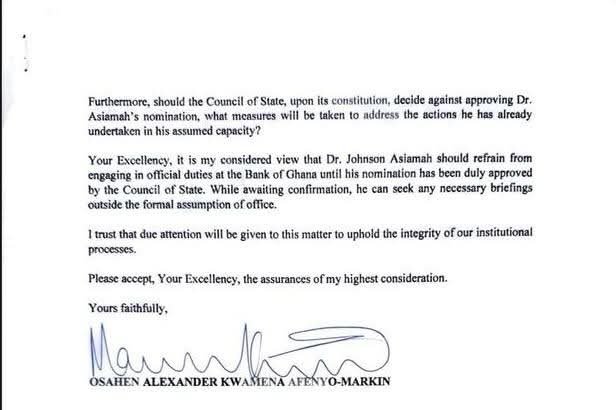

However, in a letter to President Mahama dated February 4, Minority Leader raised serious concerns with Dr. Asiamah’s assumption of office in the absence of the Council of State.

“Your Excellency, it is my considered view that Dr. Johnson Asiamah should refrain from engaging in official duties at the Bank of Ghana until his nomination has been duly approved by the Council of State. While awaiting confirmation, he can seek any necessary briefings outside the formal assumption of office,” the letter noted.

He added, “I trust that due attention will be given to this matter to uphold the integrity of our institutional processes.”

By Edem Mensah-Tsotorme

Read full statement below

News

Bagbin lifts suspension of four MPs

Speaker of Parliament, Alban Bagbin, has lifted the suspension of four Members of Parliament (MPs) who were suspended after a clash during the vetting session on Thursday, January 30, 2025.

The altercation occurred between Minority and Majority MPs, escalating tensions in Parliament. The disagreement reached a peak after the suspension of the four MPs, triggering a debate over whether the vetting should proceed on January 31, 2025.

Following the suspension, the Minority MPs walked out, leaving only the Majority to continue with the vetting of nominees, including that of MP Samuel Okudzeto Ablakwa, who had already undergone several hours of questioning by the Minority Leader, Alexander Afenyo-Markin.

The lifting of the suspension comes after a review of the incident. The four MPs – Rockson Nelson Dafeamekpor, Frank Annoh-Dompreh, Jerry Ahmed Shaib and Alhassan Tampuli – are now expected to resume their parliamentary duties as normal. The move seeks to restore order in Parliament following the disruptions.

This was after both the majority leader and minority leader appealed to the Speaker of Parliament to lift the ban on the four MPs.

Alban Bagbin said, “So I have lifted the suspension order. I do so instantly and takes effect immediately. The affected Hon. Members are permitted now to enter the precincts of the house. I must say they actually complied with the orders.”

He assured that the investigations will continue, and the House will have the opportunity to make a decision.

He commended the security agencies for their support.

Source : Citinewsroom.com